The British State’s History of Chemical Experiments on Its Own People

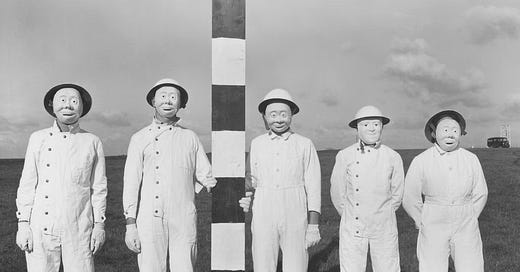

Five chemical experiments the British State used on its population.

The British government’s recent investment of £50 million into sun-dimming research — a geoengineering scheme that aims to reflect sunlight away from Earth to mitigate climate change — has rightly sparked a wave of controversy and alarm. Described by many as a bid to “block out the sun,” this radical project has been officially acknowledged, yet leaves open the question of whether it is being discussed now, and how long it has been happening. More importantly, is this just the latest in a long line of covert experiments conducted by the British state on its population?

The historical record suggests that this is not new territory. From the Cold War to the late 20th century, the UK government has repeatedly carried out chemical and biological tests involving ordinary citizens, often without their knowledge or consent. The justification has typically been “national security,” but the ethical breaches are undeniable. Below are five documented instances where British citizens were used, knowingly or not, as experimental subjects in the state’s chemical warfare research, with one infamous example still under legal scrutiny.

1. The Fluorescent Particle Trials (1953–1964)

Between 1953 and 1964, the Ministry of Defence conducted a sweeping series of tests under the name Fluorescent Particle Trials. The trials involved dispersing zinc cadmium sulphide (ZnCdS), a fluorescent compound, across large areas of the UK. Released from aircraft, ships, and vehicles, the purpose was to study how a biological or chemical attack might spread in the event of war with the Soviet Union.

The public was never informed. ZnCdS was used because it glowed under UV light, allowing researchers to track its dispersion. The Ministry claimed the substance was harmless, but cadmium is a known carcinogen. Millions of Britons were exposed.

According to a 2002 report commissioned by the government and conducted by Professor Peter Lachmann of the Royal Society, the long-term health effects of the trials remain uncertain. While the report claimed the risks were minimal, critics have pointed out that the assessments were largely based on short-term data and did not adequately account for vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, or those with pre-existing respiratory conditions.

An investigation by The Independent found that many of the tests went far beyond what was officially acknowledged. The trials were not limited to simulations. In some instances, they were intended to test how easily real chemical or biological warfare could be unleashed upon the population, cloaked under the guise of research and readiness.

2. The DICE Trials (1971–1975)

Between 1971 and 1975, the UK and US military jointly conducted a series of classified experiments on the Dorset coastline under the project name DICE — Defence Independent Chemical Evaluation. The objective was to determine how easily biological warfare agents could be disseminated over wide areas and how effectively such agents could be detected in real-time using newly developed equipment.

The location of South Dorset was chosen for its coastal geography and relative proximity to Porton Down. Over four years, the trials included the aerial and ground-level dispersal of various substances, including:

Anthrax simulants – such as Bacillus globigii (now classified as Bacillus subtilis), selected because it mimics the behaviour of anthrax spores while being considered non-lethal at the time.

Serratia marcescens – a bacterium once widely used in such trials, later linked to respiratory and urinary tract infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

Phenol – a toxic chemical compound with known corrosive and systemic effects when inhaled or absorbed through the skin.

In several test runs, military aircraft released clouds of these agents at varying altitudes and weather conditions, allowing scientists to study the radius of dispersal and how the agents behaved in real-world environments. Ground-based stations and naval ships monitored particle concentrations, with the XM19 Chemiluminescence Detector serving as the primary technology tested for rapid detection of airborne threats.

What makes the DICE trials particularly controversial is the secrecy surrounding them. No consent was sought from the public, nor were local authorities adequately informed. Residents of Dorset, including farmers, schoolchildren, and the elderly, were potentially exposed to unknown quantities of chemical and biological agents.

Government documentation declassified in the early 2000s acknowledged that Serratia marcescens and similar agents had been chosen under the assumption they posed no serious threat to health. However, later medical literature contradicted this claim. S. marcescens has since been identified as a cause of hospital-acquired infections and is known to cause pneumonia, endocarditis, and wound infections.

Concerns raised by local residents and activists in the decades since include clusters of rare illnesses and unexplained respiratory issues in communities near the test sites. Though no formal epidemiological study has yet confirmed a direct link, calls for a public inquiry into the health outcomes of DICE remain unresolved.

As with other Cold War-era experiments, the DICE trials reflect a mindset that viewed civilian populations as collateral in the pursuit of scientific and military preparedness — a justification that continues to face scrutiny.

3. The Sabotage Trials (1952–1964)

During the height of Cold War paranoia, the UK government embarked on a series of covert experiments to assess how vulnerable Britain’s infrastructure was to biological sabotage. Known collectively as the Sabotage Trials, these tests were carried out across key strategic locations — none more audacious than the London Underground.

One such trial took place in 1963 on the Northern Line. Two government scientists boarded a packed train at Colliers Wood station. As the train sped north toward Tooting Broadway, one of them discreetly dropped a small cardboard carton filled with bacterial spores out of the carriage window. Upon impact with the tunnel floor, the carton burst open, releasing millions of spores into the confined underground airspace.

The results were both revealing and alarming. Swabs taken days and even weeks later showed that the spores had spread extensively, reaching as far north as Camden Town — ten miles from the original dispersal site. The London Underground's enclosed tunnels and high passenger throughput proved to be an ideal vector for widespread contamination.

The spores used in this and similar trials were typically Bacillus globigii (now Bacillus subtilis), a bacterium commonly used as a simulant for anthrax. Officials claimed it was harmless, but later evaluations cast doubt on this assumption, particularly for immunocompromised individuals or those with respiratory conditions.

The trials were authorised by the Ministry of Defence and conducted under tight secrecy. Neither the commuters who inhaled the spores nor the station staff who cleaned the affected areas were ever informed of the tests. No consent was sought, and there was no post-trial health monitoring.

Internal documents released decades later revealed that these experiments were not one-off incidents but part of a larger programme intended to map the efficiency of biological agent dispersal in urban environments. Other sabotage simulations targeted ventilation shafts, public buildings, and transport hubs.

The ethical implications are stark. These were not merely laboratory studies but real-world experiments carried out in public spaces, with ordinary citizens used as unwitting test subjects. In the absence of oversight or informed consent, the Sabotage Trials have since become emblematic of the darker side of Cold War-era state experimentation.

No large-scale health studies have ever been conducted to track potential consequences among exposed populations, despite repeated calls from MPs, medical professionals, and activists for a retrospective inquiry. The government maintains that no harm was caused — a claim that continues to be challenged by those who question the long-term impact of repeated low-level exposure to bacterial agents in confined, poorly ventilated environments.

4. The Spider Web Particle Experiments (1964–1973)

Between 1964 and 1973, the Ministry of Defence carried out a lesser-known but deeply unsettling series of experiments across multiple British cities, including London, Southampton, and Swindon. Known colloquially as the Spider Web Particle Experiments, these trials were designed to measure the persistence and movement of airborne biological simulants in urban environments.

The concept was deceptively simple. Scientists placed spider webs inside sealed boxes in public areas, including rooftops, ventilation systems, and near public transport routes. These webs were then exposed to harmless but traceable bacteria, often Bacillus globigii or Escherichia coli strains engineered to mimic the behavior of more dangerous pathogens. The purpose was to see how these microbes would cling to surfaces, how far they would travel over time, and how long they would remain viable under varying conditions like humidity, pollution, and airflow.

Despite the apparent harmlessness of the bacterial simulants, these experiments were carried out without the public’s knowledge or informed consent. The tests often took place in areas with high pedestrian traffic, including schools, marketplaces, and city centres. Residents went about their lives unaware that they were part of a controlled military experiment on biological dispersion.

Concerns over long-term health effects began to emerge in the years that followed. Some families living in areas where tests occurred began to report clusters of rare conditions — including unexplained birth defects, autoimmune disorders, and neurological abnormalities in children. While causation has never been officially established, the correlations have raised persistent suspicions. Affected families have since called for independent investigations and greater transparency from the government, but official inquiries have consistently dismissed the possibility of a direct link.

Documents declassified in the early 2000s revealed that these experiments were part of a much broader programme to understand the feasibility of biological warfare in civilian settings. These trials were not isolated or exploratory — they were calculated and methodical, with repeated deployments in densely populated environments over nearly a decade.

The ethical questions are glaring. The public was treated as a passive subject pool for military science, exposed to live agents in conditions deliberately designed to reflect potential wartime attacks. No follow-up health monitoring was ever conducted. No letters were sent to affected neighbourhoods. The data was gathered, the reports filed, and the trials quietly buried in government archives — until they were unearthed by journalists and researchers decades later.

5. The Porton Down Human Testing Programme (1940s–1980s)

Porton Down — the Ministry of Defence’s sprawling chemical and biological warfare research facility in Wiltshire — remains one of the most secretive and controversial institutions in British military history. From the 1940s through to the 1980s, it served as the central hub for state-sponsored experiments on chemical and biological agents, many of which involved human subjects, primarily young servicemen.

Over four decades, it’s estimated that more than 20,000 British soldiers were exposed to a variety of toxic substances. While some signed up believing they were helping test cold remedies or protective clothing, many were deceived about the true nature of the trials. Informed consent, where it existed at all, was routinely incomplete, misleading, or outright false.

The substances tested at Porton Down were not benign. They included:

Sarin – a deadly nerve agent that interferes with the nervous system and causes respiratory failure

VX nerve agent – even more toxic than sarin, with effects that begin within seconds of exposure

Mustard gas – a blistering chemical used during WWI, known to cause severe burns, blindness, and cancer

CS gas – tear gas used for riot control but tested on military volunteers in varying concentrations

LSD – used in psychological experiments to assess its potential as a mind-control drug or "truth serum"

BZ and other hallucinogens – incapacitating agents tested for their effects on soldier cognition and coordination

CSM and CR gas – highly irritating agents tested on skin and eyes to simulate chemical battlefield conditions

One of the most infamous tragedies linked to Porton Down was the death of Ronald Maddison, a 20-year-old RAF engineer who died in 1953 after being exposed to sarin. Maddison had been told he was participating in research to find a cure for the common cold. He died within an hour of the test. The government quickly classified the incident, suppressing the truth for decades. Only in 2004, following persistent pressure from his family and campaigners, did a second inquest finally rule his death as “unlawful killing.”

The case of Maddison helped trigger a broader investigation into Porton Down’s human testing legacy. This culminated in Operation Antler, a major police inquiry launched in the late 1990s. Investigators reviewed thousands of documents and interviewed hundreds of former test subjects. What emerged was a damning picture of systemic ethical violations: long-term health consequences including cancer, neurological damage, psychological trauma, and, in some cases, early death.

In 2006, the Ministry of Defence issued a formal statement of regret, stopping short of a full apology. It also began offering compensation payments to affected individuals, but only those who could prove participation and harm, an often insurmountable hurdle given the age of the cases and the Ministry’s reluctance to release full documentation.

To this day, Porton Down remains operational. It continues to conduct research on pathogens, toxins, and protective technologies, albeit under tighter regulation. Yet its legacy is still shrouded in secrecy. Thousands of former servicemen have alleged they were manipulated or used as test subjects without proper consent. Many claim they were offered no follow-up care, no medical monitoring, and no recognition.

The British state has never held a public inquiry into the full scope of human experimentation at Porton Down.

Makes you think whenever you hear about outbreaks of “legionnaires disease” could it be these ongoing experiments

Operation Large Area Coverage (LAC), conducted in the late 1950s, involved the U.S. Army Chemical Corps dispersing zinc cadmium sulfide (ZnCdS) particles over large areas of the United States and Canada. This was part of a larger program to test the dispersal patterns and geographic reach of potential chemical or biological weapons.

The Tuskegee Experiments.

Check out the number of doctors from the Concentration Camps who were imported as part of Operation Paperclip.

The Western Governments have been engaged in this horrific pattern of behavior against their own citizens for quite some time.